Status of this This

Document

This section describes the status of this document at the

time of its publication. Other documents may supersede this

document. A list of current W3C publications and the latest

revision of this technical report can be found in the W3C technical reports index at

http://www.w3.org/TR/.

This document is joint work of

a Working Group Note produced jointly

by the W3C Semantic

Web Deployment Working Group [ SWD-WG ]

and the W3C XHTML2 Working

Group [ XHTML2-WG ]. This work is part

of both the W3C Semantic Web

Activity and the HTML

Activity . The two Working Groups

expect transition of this

document to advance Working Group Note occurs simultaneously with the

transition of the RDFa Syntax

syntax specification to Recommendation Status and then publish a final version

of this Primer as a W3C Working Group

Note. Recommendation.

This version of the RDFa Primer is a major

rewrite contains small editorial

changes to simplify the presentation.

This primer is now fully in step with the Candidate Recommendation previous version of the RDFa

Syntax specification [ RDFa-SYNTAX as

well as a short additional section ( 4.1 ]. ) providing pointers to

those wishing to create new relationship vocabularies. The changes

are detailed in a differences document . The Working Groups

expect to publish a final version of

have received suggestions that this

document as a Working Group Note after

be expanded and the RDFa Syntax specification is advanced Groups may add to W3C

Proposed Recommendation. it in the

future but are not committing to do so.

Comments on this Working Draft

Group Note are welcome and may be sent

to public-rdf-in-xhtml-tf@w3.org

; please include the text "comment" in the subject line. All

messages received at this address are viewable in a public

archive .

Publication as a Working Group Note does

not imply endorsement by the W3C Membership. This is a draft

document and may be updated, replaced or obsoleted by other

documents at any time. It is inappropriate to cite this document as

other than work in progress.

This document was produced groups operating under the 5 February

2004 W3C Patent Policy . W3C maintains a public list

of any patent disclosures made in connection with the

deliverables of the XHTML 2 group and another public list

of any patent disclosures made in connection with the

deliverables of the Semantic Web Deployment Working Group; those

pages also include instructions for disclosing a patent. An

individual who has actual knowledge of a patent which the

individual believes contains

Essential Claim(s) must disclose the information in accordance

with

section 6 of the W3C Patent Policy .

Publication as a Working Draft does not imply

endorsement by the W3C Membership. This is a draft document and may

be updated, replaced or obsoleted by other documents at any time.

It is inappropriate to cite this document as other than work in

progress.

1 Introduction

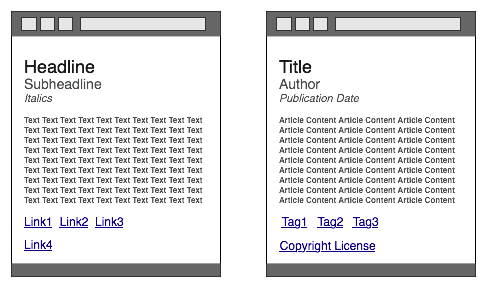

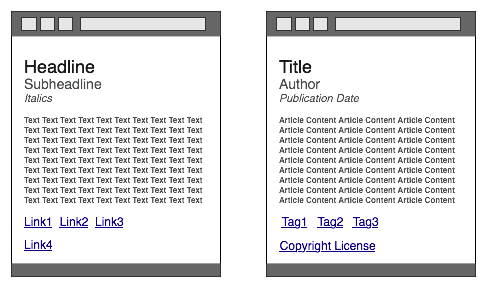

The web is a rich, distributed repository of interconnected

information organized primarily for human consumption. On a typical

web page, an HTML XHTML author might specify a headline, then a

smaller sub-headline, a block of italicized text, a few paragraphs

of average-size text, and, finally, a few single-word links. Web

browsers will follow these presentation instructions faithfully.

However, only the human mind understands that the headline is, in

fact, the blog post title, the sub-headline indicates the author,

the italicized text is the article's publication date, and the

single-word links are categorization labels. The gap between what

programs and humans understand is large.

On the left, what browsers see. On the

right, what humans see. Can we bridge the gap so browsers see more

of what we see?

|

What if the browser received information on the meaning of a web

page's visual elements? A dinner party announced on a blog could be

easily copied to the user's calendar, an author's complete contact

information to the user's address book. Users could automatically

recall previously browsed articles according to categorization

labels (often called tags). A photo copied and pasted from a web

site to a school report would carry with it a link back to the

photographer, giving her proper credit. When web data meant for

humans is augmented with hints meant for computer programs, these

programs become significantly more helpful, because they begin to

understand more of the data's

structure.

RDFa allows HTML XHTML authors to do just that. Using a few simple

HTML XHTML

attributes, authors can mark up human-readable data with

machine-readable indicators for browsers and other programs to

interpret. A web page can include markup for items as simple as the

title of an article, or as complex as a user's complete social

network.

RDFa benefits from the extensive power of RDF [RDF] , the W3C's standard for interoperable

machine-readable data. However, readers of this document are not

expected to understand RDF. Readers are expected to

understand at least a basic level of XHTML.

1.1

HTML vs. XHTML

To date, because XHTML is extensible while

HTML is not, RDFa has only been specified for XHTML 1.1. Web

publishers are welcome to use RDFa markup inside HTML4: the design

of RDFa anticipates this use case, and most RDFa parsers will

recognize RDFa attributes in any version of HTML. The authors know of no deployed Web browser that will

fail to present an HTML document as intended after adding RDFa

markup to the document. However, publishers should be aware that

RDFa will not validate in HTML4 at this time. RDFa attributes

validate in XHTML, using the XHTML1.1+RDFa DTD.

2 Adding Flavor to

HTML XHTML

Consider Alice, a blogger who publishes a mix of professional

and personal articles at http://example.com/alice .

We will construct markup examples to

illustrate how Alice can use RDFa. The complete markup of these

examples can be viewed independently .

2.1 Licensing your

Work

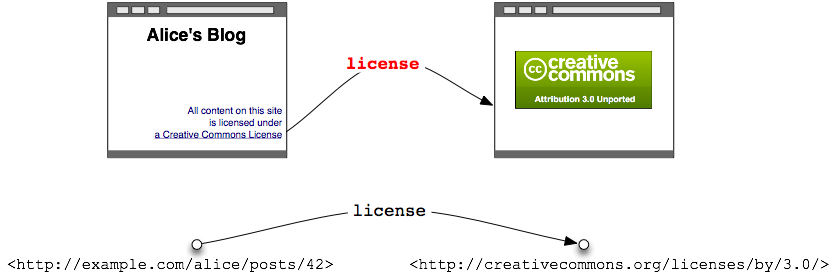

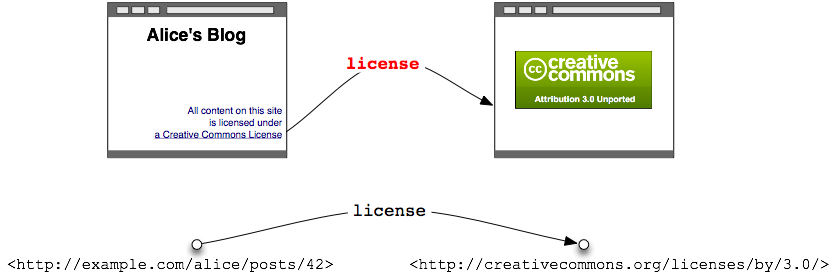

In her blog's footer, Alice declares her content to be freely

reusable, as long as she receives due credit when her articles are

cited. The HTML XHTML includes a link to an

appropriate a Creative Commons

[CC] license:

...

All content on this site is licensed under

<a href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/">

a Creative Commons License

</a>.

A human clearly understands this sentence, in particular the

meaning of the link with respect to the current document:

it indicates the document's license, the conditions under which the

page's contents are distributed. Unfortunately, when Bob visits

Alice's blog, his browser sees only a plain link that could just as

well point to one of Alice's friends or to her resume. For Bob's

browser to understand that this link actually points to the

document's licensing terms, Alice needs to add some flavor

, some indication of what kind of link this is.

She can add this flavor using the rel HTML attribute (which we'll write as

@rel so as not to repeat the word "attribute" too

often), which defines the relationship between the current

page and the linked page. The value of the attribute is

license , a HTML

an XHTML keyword reserved for just this

purpose:

...

All content on this site is licensed under

<a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/">

a Creative Commons License

</a>.

With this small update, Bob's browser will now understand that

this link has a flavor: it indicates the blog's license.

A link with flavor: the link indicates the

web page's license. We can represent web pages as nodes, the link

as an arrow connecting those nodes, and the link's flavor as the

label on that arrow.

|

2.2 Labeling the Title and

Author

Alice is happy that adding HTML

XHTML flavor lets Bob find the

copyright license on her work quite easily. But what about the

article title and author name? Here, instead of marking up a link,

Alice wants to augment existing text within the page. The title is

an HTML a

headline, and her name a sub-headline:

<div>

<h2>The trouble with Bob</h2>

<h3>Alice</h3>

...

</div>

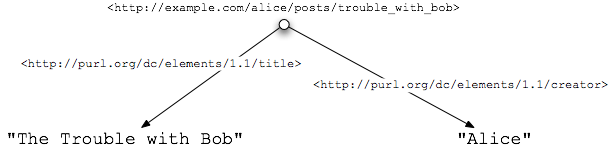

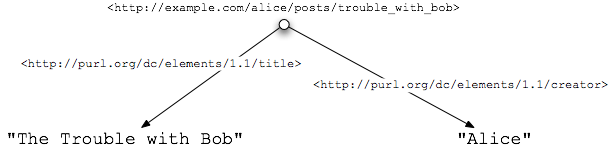

To indicate that h2 represents the title of the

page, and h3 the author, Alice uses

@property , an attribute introduced by RDFa for the

specific purpose of marking up existing text in an HTML XHTML page.

<div xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/">

<h2 property="dc:title">The trouble with Bob</h2>

<h3 property="dc:creator">Alice</h3>

...

</div>

Why use dc:creator and dc:title ,

instead of simply creator and title ? As

it turns out, HTML XHTML does not have reserved keywords for those

two concepts. Alice could boldly choose to write

property="title" , but how does a program reading this

know whether "title" here refers to the title of a work, a job

title, or the deed of a piece of

for some real-estate property? And, if

every web publisher laid claim to their own short keywords, the

world of available properties would become quite messy, a bit like

saving every file on a computer's desktop without any directory

structure to organize them.

To enforce a modicum of organization, RDFa does not recognize

property="title" . Instead, Alice must indicate a

directory somewhere on the web, using simply a URL, from where to

import the specific creator and title

concepts she means to express. Fortunately, the Dublin Core

[DC] community has already defined a vocabulary

of useful concepts for describing documents, including both

creator and title , where

title indeed means the title of a work. So, Alice:

- imports the Dublin Core vocabulary using

xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/" , which

associates the prefix dc with the URL

http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/ , and

- uses

dc:creator and dc:title . These

are short-hands for the full URLs

http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/creator , and

http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/title .

In RDFa, all property names are, in fact, URLs.

Literal Properties: RDFa lets Alice connect

not just one URL to another—for example to connect her blog entry

URL to the Creative Commons license URL— but also to connect one

URL to a string such as "The Trouble with Bob". All arrows are

labeled with the corresponding property name, which is also a

URL.

|

2.3 Multiple Items per

Page

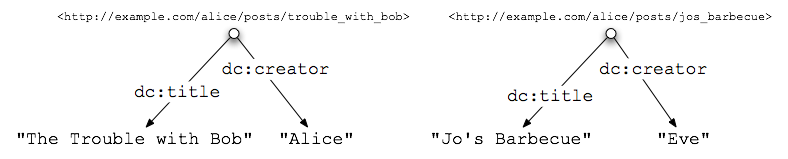

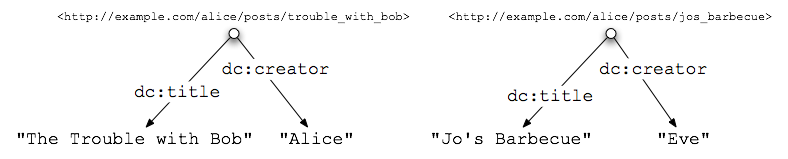

Alice's blog contains, of course, multiple entries. Sometimes,

Alice's sister Eve guest blogs, too. The front page of the blog

lists the 10 most recent entries, each with its own title, author,

and introductory paragraph. How, then, should Alice mark up the

title of each of these entries individually even though they all

appear within the same HTML web page? RDFa provides @about , an

attribute for specifying the exact URL to which the contained RDFa

markup applies:

<div xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/">

<div >

<div about="/alice/posts/trouble_with_bob">

<h2 property="dc:title">The trouble with Bob</h2>

<h3 property="dc:creator">Alice</h3>

...

</div>

<div >

<div about="/alice/posts/jos_barbecue">

<h2 property="dc:title">Jo's Barbecue</h2>

<h3 property="dc:creator">Eve</h3>

...

</div>

...

</div>

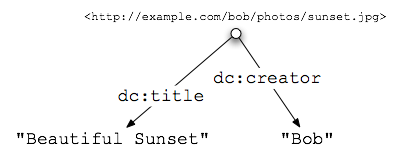

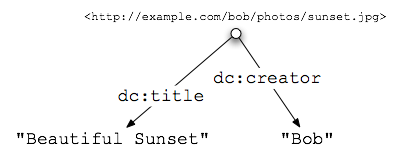

We can represent this, once again, as a diagram connecting URLs

to properties:

Multiple Items per Page: each blog entry is

represented by its own node, with properties attached to each. Here

we've used the short-hands to label the arrows, in order to save

space and clarify the diagram. The actual labels are always the

full URLs.

|

Alice can use the same technique to give her friend Bob proper

credit when she posts one of his photos: <div about="/posts/trouble_with_bob">

<div about="/alice/posts/trouble_with_bob">

<h2 property="dc:title">The trouble with Bob</h2>

The trouble with Bob is that he takes much better photos than I do:

<div about="http://example.com/bob/photos/sunset.jpg">

<img src="http://example.com/bob/photos/sunset.jpg" />

<span property="dc:title">Beautiful Sunset</span>

by <span property="dc:creator">Bob</span>.

</div>

</div>

Notice how the innermost @about value,

http://example.com/bob/photos/sunset.jpg , "overrides"

the outer value /posts/trouble_with_bob /alice/posts/trouble_with_bobHTML markup

inside the innermost div

with the corresponding @about .

And, once again, as a diagram that abstractly represents the

underlying data of this new portion of markup:

Describing a Photo

|

3 Going Deeper

In addition, Alice wants to make information about herself

(email address, phone number, etc.) easily available to her

friends' contact management software. This time, instead of

describing the properties of a web page, she's going to describe

the properties of a person: herself. To do this, she adds deeper

structure, so that she can connect multiple items that themselves

have properties.

3.1 Contact

Information

Alice already has contact information displayed on her blog.

<div>

<p>

Alice Birpemswick

</p>

<p>

Email: <a href="mailto:alice@example.com">alice@example.com</a>

</p>

<p>

Phone: <a href="tel:+1-617-555-7332">+1 617.555.7332</a>

</p>

</div>

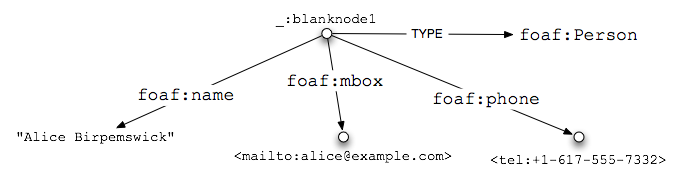

The Dublin Core vocabulary does not provide property names for

describing contact information, but the Friend-of-a-Friend [FOAF] vocabulary does. In RDFa, it is common and easy

to combine different vocabularies in a single page. Alice imports

the FOAF vocabulary and declares a foaf:Person . For

this purpose, Alice uses @typeof , an RDFa attribute

that is specifically meant to declare a new data item with a

certain type:

<div typeof="foaf:Person" xmlns:foaf="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/">

...

Then, Alice can indicate which content on the page represents

her full name, email address, and phone number:

<div typeof="foaf:Person" xmlns:foaf="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/">

<p property="foaf:name">

Alice Birpemswick

</p>

<p>

Email: <a rel="foaf:mbox" href="mailto:alice@example.com">alice@example.com</a>

</p>

<p>

Phone: <a rel="foaf:phone" href="tel:+1-617-555-7332">+1 617.555.7332</a>

</p>

</div>

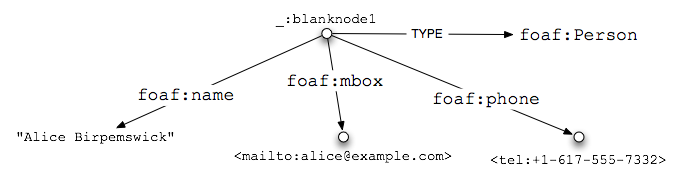

Note how Alice didn't specify @about like she did

when adding blog entry metadata. What is she associating these

properties with, then? In fact, the @typeof on the

enclosing div implicitly sets the subject of the

properties marked up within that div . The name, email

address, and phone number are associated with a new node of type

foaf:Person . This node has no URL to identify it, so

it is called a blank node .

A Blank Node: blank nodes are not

identified by URL. Instead, many of them have a @typeof attribute

that identifies the type of data they represent. This

approach—providing no name but adding a type— is particularly

useful when listing a number of items on a page, e.g. calendar

events, authors on an article, friends on a social network,

etc.

|

3.2 Social Network

Next, Alice wants to add information about her friends,

including at least their names and homepages. Her plain HTML XHTML is:

<div>

<ul>

<li>

<a href="http://example.com/bob/">Bob</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="http://example.com/eve/">Eve</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="http://example.com/manu/">Manu</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

First, Alice indicates that all of these friends are of type

foaf:Person .

<div xmlns:foaf="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/">

<ul>

<li typeof="foaf:Person">

<a href="http://example.com/bob/">Bob</a>

</li>

<li typeof="foaf:Person">

<a href="http://example.com/eve/">Eve</a>

</li>

<li typeof="foaf:Person">

<a href="http://example.com/manu/">Manu</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

Beyond declaring the type of data we're dealing with, each

@typeof creates a new blank node with its own distinct

properties, all without having to provide URL identifiers. Thus,

Alice can easily indicate each friend's homepage:

<div xmlns:foaf="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/">

<ul>

<li typeof="foaf:Person">

<a rel="foaf:homepage" href="http://example.com/bob/">Bob</a>

</li>

<li typeof="foaf:Person">

<a rel="foaf:homepage" href="http://example.com/eve/">Eve</a>

</li>

<li typeof="foaf:Person">

<a rel="foaf:homepage" href="http://example.com/manu/">Manu</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

And, of course, each friend's name:

<div xmlns:foaf="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/">

<ul>

<li typeof="foaf:Person">

<a property="foaf:name" rel="foaf:homepage" href="http://example.com/bob/">Bob</a>

</li>

<li typeof="foaf:Person">

<a property="foaf:name" rel="foaf:homepage" href="http://example.com/eve/">Eve</a>

</li>

<li typeof="foaf:Person">

<a property="foaf:name" rel="foaf:homepage" href="http://example.com/manu/">Manu</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

Using @property , Alice specifies that the linked

text ("Bob", "Eve", and "Manu") are, in fact, her friends' names.

With @rel , she indicates that the clickable links are

her friends' homepages. Alice is ecstatic that, with so little

additional markup, she's able to fully express both a pleasant

human-readable page and a machine-readable dataset.

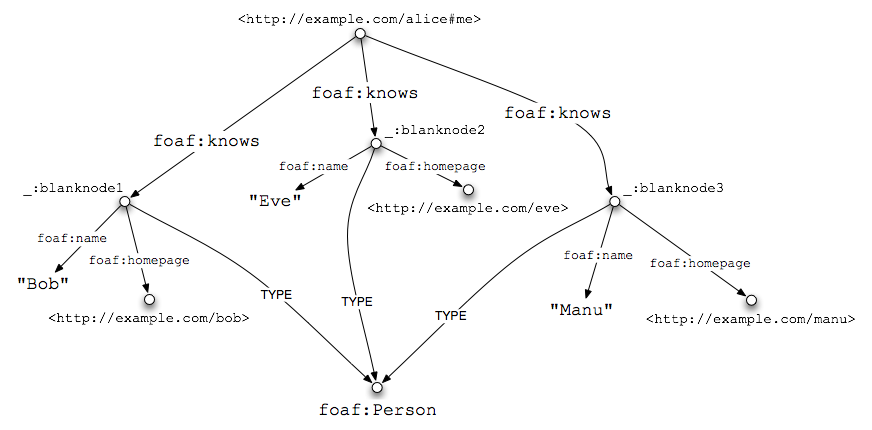

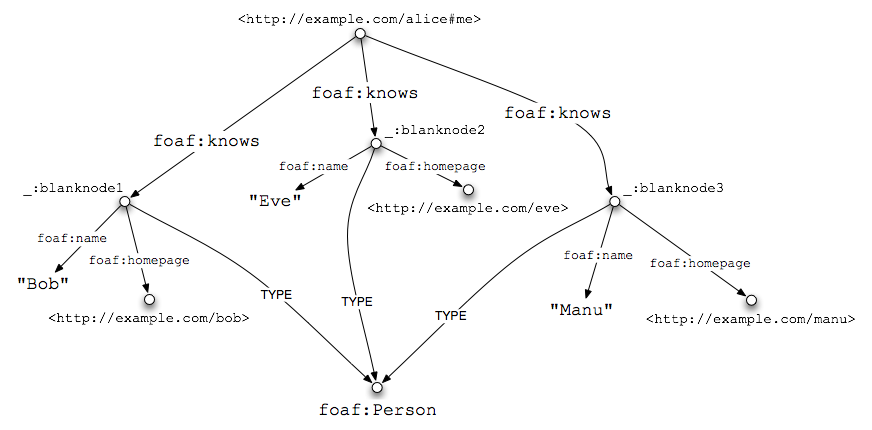

Alice is tired of repeatedly entering information about her

friends in each new social networking sites. With RDFa, she can

indicate her friendships on her own web page, and let social

networking applications read it automatically. So far, Alice has

listed three individuals but has not specified her relationship

with them; they might be her friends,

or they might be her favorite 17th century poets. To indicate that

she, in fact, knows them, she uses the FOAF property

foaf:knows :

<div xmlns:foaf="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/" about="#me" rel="foaf:knows">

<ul>

<li typeof="foaf:Person">

<a property="foaf:name" rel="foaf:homepage" href="http://example.com/bob">Bob</a>

</li>

<li typeof="foaf:Person">

<a property="foaf:name" rel="foaf:homepage" href="http://example.com/eve">Eve</a>

</li>

<li typeof="foaf:Person">

<a property="foaf:name" rel="foaf:homepage" href="http://example.com/manu">Manu</a>

</li>

</ul>

</div>

Using rel="foaf:knows" once is enough to

connect Bob, Eve, and Manu to Alice. This is achieved thanks to the

RDFa concept of chaining : because the top-level

@rel is without a corresponding @href ,

it connects to any contained node, in this case the three nodes

defined by @typeof . (The @about="#me" is

a FOAF/RDF convention: the URL that represents the person

Alice is http://example.com/alice#me . It should not

be confused with Alice's homepage,

http://example.com/alice . You are what you eat, but

you are far more than just your homepage.)

Alice's Social Network

|

4 You Said Something about

RDF?

RDF, the Resource Description Framework, is exactly the abstract

data representation we've drawn out as graphs in the above

examples. Each arrow in the graph is represented as a

subject-predicate-object triple: the subject is the node at the

start of the arrow, the predicate is the arrow itself, and the

object is the node or literal at the end of the arrow. An RDF

dataset is often called an "RDF graph", and it is typically stored

in what is often called a "Triple Store."

Consider the first example graph:

The two RDF triples for this graph are written, using the

Notation3 syntax [N3] , as follows: <http://www.example.com/alice/posts/42>

<http://www.example.com/alice/posts/trouble_with_bob>

<http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/title> "The Trouble with Bob";

<http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/creator> "Alice" .

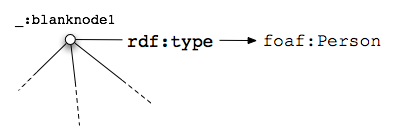

Also, the TYPE arrows we drew are no different from

other arrows, only their label is actually a core RDF property,

rdf:type , where the rdf namespace is

<http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> .

The contact information example from above should thus be

diagrammed as:

The point of RDF is to provide a universal language for

expressing data. A unit of data can have any number of fields, and

field names are URLs which can be reused by any publisher, much

like any web publisher can link to any web page, even ones they did

not create themselves. Given data, in the form of RDF triples,

collected from various locations, and using the RDF query language

SPARQL [SPARQL] , one can search for "friends of

Alice's who created items whose title contains the word 'Bob',"

whether those items are blog posts, videos, calendar events, or

other data types we haven't thought of yet.

RDF is an abstract, machine-readable data representation meant

to maximize the reuse of vocabularies. RDFa is a way to express RDF

data within HTML, XHTML, by reusing the existing human-readable

data.

4.1

Custom Vocabularies

As Alice marks up her page with RDFa, she

may discover the need to express data, e.g. her favorite photos,

that is not covered by existing vocabularies like Dublin Core or

FOAF. Since RDFa is simply a representation of RDF, the RDF schema

mechanism that enables RDF extensibility is the same that enables

RDFa extensibility. Once an RDF vocabulary created, it can be used

in RDFa markup just like existing vocabularies.

The instructions on how to create an RDF

schema are available in Section 5 of the RDF Primer [RDF-SCHEMA-PRIMER] .At

a high level, the creation of an RDF schema for RDFa

involves:

- Selecting a URL where the vocabulary will

reside, e.g.

http://example.com/photos/vocab# .

- Distributing and RDF document, at that

URL, which defines the classes and properties that make up the

vocabulary. For example, Alice may want to define classes

Photo and Camera ,as well as

the property takenWith that

relates a photo to the camera with which it was taken.

- Using the vocabulary in XHTML+RDFa with

the usual prefix declaration mechanism, e.g.

xmlns:photo="http://example.com/photos/vocab#"

,and typeof="photo:Camera" .

It is worth noting that anyone who can

publish a document on the Web can publish an RDF vocabulary and

thus define new data fields they may wish to express. RDF and RDFa

allow fully distributed extensibility of vocabularies.

5 Find Out More

More examples, links to tools, and information on how to get

involved can be found on the the

RDFa Wiki .

6 Acknowledgments

This document is the work of the RDF-in-HTML Task Force,

including (in alphabetical order) Ben Adida, Mark Birbeck, Jeremy

Carroll, Michael Hausenblas, Shane McCarron, Steven Pemberton, Manu

Sporny, Ralph Swick, and Elias Torres. This work would not have

been possible without the help of the Semantic Deployment Working

Group and its previous incarnation, the Semantic Web Deployment and

Best Practices Working Group, in particular chairs Tom Baker and

Guus Schreiber (and prior chair David Wood), the XHTML2 Working

Group, Eric Miller, previous head of the Semantic Web Activity, and

Ivan Herman, current head of the Semantic Web Activity. Earlier

versions of this document were officially reviewed by Gary Ng and

David Booth, and more recent versions by Diego Berrueta and Ed

Summers, all of whom provided insightful comments that

significantly improved the work. Bob DuCharme also reviewed the

work and provided useful commentary.